Sex Workers Decry ‘Moral Panic’ Over Human Trafficking by Victoria Mckenzie

At the height of national outrage over what government officials and activists call a human trafficking “epidemic,” sex workers are challenging what they say are misleading and harmful efforts to link prostitution to sex trafficking.

“People have used this moral panic, this idea that there is a trafficking epidemic, to create so much funding and so much policy that now that they’re being pressured to show the evidence—to show the sex trafficking arrests,” said Tara Burns, researcher and founding member of the Community United for Safety and Protection (CUSP), a group of former and current Alaska sex workers allied with sex trafficking victims.

That’s where we see police arresting [prostitutes] for sex trafficking themselves, just so they can get those sex trafficking numbers up, and match the moral panic they’ve created.”

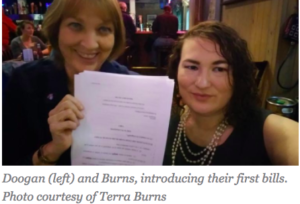

CUSP is lobbying for the passage of companion bills (HB 112/SB 73) in the Alaska Senate and House which would expand sexual assault laws to explicitly prohibit law enforcement from sexual contact with trafficking or domestic violence victims—as part of its continuing campaign to protect sex workers from laws that make them “vulnerable to violence and exploitation.”

In California, another group is challenging a state law that criminalizes prostitution, and asking a federal court to allow for a closer examination of studies that link consensual sex work to sex trafficking.

In January, a three-judge panel in the 9th circuit dismissed a suit by the Sex Workers and Erotic Service Providers Legal, Educational and Research Project (ESPLERP) to declare unconstitutional state laws that make prostitution a crime. The panel sided with 13 state and national organizations that wrote in to oppose ESPLERP, arguing that prostitution needs to remain criminalized in order to combat the “attendant evils” of violence against women, drug abuse—and above all, sex-trafficking.

ESPLERP filed for a rehearing before the full 9th circuit on January 31, wanting the court to subject the studies it cited to a higher standard of review. But in an era when pornography has been declared a “public health crisis” linked to modern-day slavery, researchers who do not openly condemn prostitution are fighting an uphill battle—and sex workers themselves find it hard to be heard over the din of victims’ advocates who would speak for them.

Maxine Doogan, the founder of ESPLERP, says that denying sex workers equal protection under the law has led directly to abuse by police and other authorities and that she and other people in the industry cannot report actual cases of forced trafficking without fearing arrest themselves.

“There are many people, many women, that I know who are prostitutes, who have been caught up in these prostitution sting operations; and have been sexually assaulted by the police, and raped,” she said in an interview with The Crime Report.

“Our activity is illegal. and so that just gives license for anybody to do anything to us that they want at any time, and get away with it.”

In the document submitted to the California court, opposition groups argued that “prostitution is sexual coercion, and closely related to sex trafficking,” and that “decriminalization of prostitution will legitimize sex trafficking.”

The authors of the opposition brief cited numerous “authorities” for their argument, identifying in particular eight publications by Melissa Farley, a clinical psychologist and anti-pornography activist well known for her view that sex work is “a particularly lethal form of male violence against women,” and an expression of “male hatred of the female body.”

“To the extent that any woman is assumed to have freely chosen prostitution, then it follows that enjoyment of domination and rape are in her nature,” Farley wrote in a 2000 article for Women & Criminal Justice.

But according to independent scholars in the field, the majority of the publications cited in the opposition brief have not only been debunked but also discredited in the Canadian Supreme Court during cross-examination

The court subsequently struck down Canada’s anti-prostitution laws, finding them unconstitutional because of the negative impact they had on the safety and lives of sex workers.

Doogan notes that victim advocates are “not challenging the men who really have control over our world.”

She added: “They want to dismiss the sexual violence that we’re talking about that goes on with police.”

Doogan and other sex-worker advocates argue that the majority of people being rounded up and arrested during anti-sex-trafficking sweeps such as Operation Cross Country are not slaves held in bondage, but women working together, or as independent prostitutes– a claim supported by investigative journalists following this arrest data.

CUSP’s Terra Burns, who has analyzed thousands of charging documents from several states over the past five years, said that the most serious cases of child sex trafficking “are for the most part, not cases that are being found in prostitution stings, [but] cases that are being found because somebody came forward and made a report.”

And in jurisdictions that aren’t aggressively charging people for prostitution, more sex workers are coming to police with tips, she added.

Burns, who herself was sex trafficked as a child, has lobbied extensively for legislative amendments in Alaska. She helped push through bills at the state and county level to allow immunity for sex workers reporting a crime and hopes Alaska legislators will place priority on the proposed measure to make it illegal for police to sexually penetrate someone they were investigating.

“When an officer coerces you into having sex with him under the threat of arrest, or another kind of threat, that is an act of violence.”

“When an officer coerces you into having sex with him under the threat of arrest, or another kind of threat, that is an act of violence,” Burns said.

Police don’t need to have sex with someone in order to charge them with prostitution, but it happens. She describes one charging document where a police officer paid for a hand job at a massage parlor. “They could have arrested her right there, but instead he waited and got a hand job. and then he put her in handcuffs. And when that happens, it’s really traumatic.”

Other charging documents, published on CUSP’s website, describe police having multiple sex acts with women before arresting them.

The Alaska Department of Law, as well as the Anchorage police, continue to oppose the no-sexual-contact bill, and it has stalled for almost a year.

See also: ‘Invisible No More:’ The Other Women #MeToo Should Defend

In addition to government task forces, the anti-trafficking movement has also created a $47 million cottage industry of victim advocacy.

Significantly, in order to receive funding, organizations are still being asked to sign a Bush-era anti-prostitution pledge (also known as the “global gag rule”), even though it was ruled unconstitutional in a 2013 Supreme Court decision.

The same goes for researchers, according to George Washington University sociologist Ronald Weitzer, who has studied the sex industry and human trafficking for over three decades, and who served as an expert witness in the case before Canada’s Supreme Court. Before the gag rule was overturned, he was asked to sign the pledge in order to conduct an academic literature review for the National Institute of Justice.

“It’s shocking that even something as mundane as a literature review in this area becomes politicized,” he told The Crime Report.

More recent examples include University of Nevada researcher Barbara Brent, who was part of a 2014 task force developing a trafficking education program for first responders in Nevada.

In an email to The Crime Report, she wrote: “Participants, including Las Vegas Metropolitan Police, who receive federal trafficking funds, indicated that I could not include sex worker rights organizations on the team to develop programs because that violated their grant agreement. The task force eventually fizzled out, and I don’t know what happened to those efforts.”

Last year, the New Hampshire Human Trafficking Collaborative Task Force broke ties with its grants manager, Kate D’Amato, for apparently supporting decriminalization during a public event. The Manchester Police Department said D’Amato’s opinions violated a federal grant, though it is unclear whether that claim was ever challenged.

“What it means is often you’ll get religious or evangelical organizations, both in the US and internationally, to get funding for anti-trafficking work but have very little expertise in the area,” said Weitzer.

“And this was a major criticism of the Bush administration funding for many of these anti-trafficking organizations during that period.”

For example, Priceless Alaska, a Christian anti-trafficking organization that works closely with law enforcement, engages a team of volunteer mentors to work with trafficking victims. By way of preparation, mentors receive a three-day training. According to its website, the training “focuses on the mentor’s personal spiritual development first and sex trafficking-specific training second.”

Among the organizations that signed on to the ESPLERP opposition brief was Covenant House, the largest privately funded agency in the US that provides services to homeless and runaway youth. Last year, Covenant House worked with Loyola University to produce a multi-city report on forced labor and sex trafficking. The report claims that one in every 5 homeless youth are victims of human trafficking.

In Anchorage, that number was even higher: “Study: 1 in 4 homeless youths in Anchorage victims of human trafficking,” the local headline read.

But Burns, who has been collecting state and county arrest records for over five years, says that the data don’t add up and that the report is intentionally misleading.

“Nobody’s been charged with trafficking a minor in Alaska since 2008,” she told The Crime Report.

In 2014, following the national trend, Alaska created the Special Crimes Investigation Unit, which is devoted to finding and rescuing juveniles who are being trafficked for commercial sex.

“They’ve existed with that mission for four years now,” said Burns, “and have yet to charge anybody with trafficking a minor.”

The problem with the Loyola report, according to Burns, is the way it switches between various definitions of a sex trafficking victim; from youth that are not involved in the commercial sex industry at all, “youths that are underage and just trading sex for survival means,” and youths who are being coerced or held in bondage and commercially trafficked.

“If [Loyola researchers] had talked to a youth who actively had a violent pimp, they would have had to report that to police and the police would have gone in— because they’ve been looking to charge somebody with trafficking a minor, obviously, to support all this rhetoric. We would see some charges if it were actually going on in that way,” Burns said.

But when “you’re not being honest about what you’re actually talking about, and then you’re turning around and saying ‘oh these kids are being kidnapped by pimps and forced into prostitution’— then the policy that ends up being created is not going to serve those actually kids that really exist–that are out there having survival sex right now.”

Fundamentally, Burns believes that this study—and others like it—are compromised by the “religious agenda” underlying the moral campaign.

“Covenant House and Loyola University are both religious organizations who have a religious agenda to prevent other people from having sex that they disapprove of,” she said.

What Burns has found by looking at thousands of charging documents is that the majority of people arrested in “sex trafficking” stings are women working together as prostitutes, or with a driver—both things that increase safety in the sex industry, she says.

Just three people were charged with sex trafficking in the first two years of Alaska’s new sex-trafficking law. One was a dancer charged with sex trafficking herself, according to records Burns obtained.

Another was Amber Batts, the owner of the online escort service Sensual Alaska. Prosecutors were unable to charge her with force, fraud, or coercion since people were working for the service of their own free will– but they still convicted her on charges of 2nd-degree sex trafficking. She was sentenced to five years in prison.

“When you think of sex trafficking, you think of people that are held against their will and made to do things that they don’t want to do,” Batts’ sister, Tiana Escalante, told The Crime Report.

Escalante described being shocked to learn that a woman can be charged with sex trafficking in Alaska for a consensual act—even when she is working independently.

“I think it’s kind of outrageous. It’s her body, her right to choose.”

Meanwhile, despite the funding for sex trafficking “rescue” operations, Burns says that as a first responder she has been unable to get law enforcement to investigate two recent cases where victims were held against their will and sold for sex. In the first case, she said the FBI told her there was not enough evidence.

“I’ve been involved in or around criminal investigations for quite a bit,” she said. “There was so much evidence, there were text messages.”

In the second case, she said, despite having an admission from a violent pimp on social media, “the FBI told me they didn’t have time.”

A year ago, Burns helped one victim who was violently trafficked make a report to the FBI, and managed to get her money from the state Victims of Violent Crimes Compensation Fund.

“But the people from the violent crime compensation board actually called me up and let me know, ‘you won’t be able to receive this money on her behalf because we can’t give money to organizations that don’t oppose prostitution,’” she said.

Describing people who have illegal sex as being incapable of making a choice, or too corrupted to understand their own victimhood, isn’t a new strategy.

“It’s very similar if you look at the history of the laws against gay sex and the stigma around gay people… you look back and remember [people said] ‘well, there’s only gay because they were abused as children. And so the gay people are going to go out and they’re going to rape our children,’” Burns said.

“That’s the same kind of stigma that we see around the sex work. Well, prostitutes are all either victims, or they started out as victims and now they’re going to go and victimize somebody else.

“Imagine if you saw the same kind of rhetoric around domestic violence victims. Saying that domestic violence victims need to be arrested because they’re too morally damaged to know what’s good for them.”

This is precisely what Doogan and her cohort are trying to face down in court. As a sex worker and founder of ESPLERP, she insists that she is not a victim.

“If you were a victim advocate, I wouldn’t even bother talking to you,” she told The Crime Report. She calls them the “Anti’s.” “I think that they’re extremely tone deaf.”

“They’re treating us like the sex slaves that they think that we are. That’s the problem with their approach. I stopped talking to them because they don’t want to hear, and take responsibility for their own exploitative behavior.Members of the media are some of the worst perpetrators of this narrative violence, says Doogan, “renaming us, reclassifying us, stripping us of our agency.

“We have been barred from our own authority on these issues.”